By Alex Diggins

Friday 12 June 2020

Published on WIRED.co.uk

Herianus Herianus / EyeEm / Getty Images

The goods are stashed in a warehouse on the scruffy outskirts of the Spanish city of Santander. An anonymous building far from the hubbub of holidaymakers on the beach – and from the eyes of the authorities. Inside, it’s dimly lit and quiet. The only sounds are the low hum of electrics and the gurgle of running water. Rows of suitcases line the walls.

The couriers arrive in ones and twos, dressed as tourists to avoid detection. Once at the warehouse, they collect a suitcase and drive to the airport to catch the next plane back to Hong Kong. Hidden from border agents, what they have stashed in their luggage is worth a small fortune. But the groaning suitcases aren’t loaded with drugs or diamonds. Instead these traffickers are smuggling something altogether slimier: European eels.

There is big money in eel smuggling. The illegal global trade in European eels is worth up to £2.5 billion each year. In February this year, Gilbert Khoo, a Malaysian-born seafood trader, was convicted of moving £53 million worth of eels through the UK. Between 2015 and 2017, Khoo snuck 6.5 tons of live baby eels – called ‘glass eels’ – past British border force agents. The eels were caught off the coast of Spain. Khoo then shipped them into the UK and stashed them in a warehouse in Gloucestershire, before flying them out to Hong Kong. There, they were destined for clandestine Chinese farms where they would be reared for dining tables across South-East Asia and beyond.

It has been illegal to move the critically endangered European eel, Anguilla anguilla, outside of the EU since 2010. And even inside Europe, where the transport of European eels and sale of their meat is legal, the trade is tightly regulated. Khoo, though, pleaded ignorance to the authorities: he claimed simply to be a middleman for buying and selling seafood. But, like Al Capone, his operation was undone through shoddy paperwork – an investigation by the National Crime Agency (NCA) found Khoo had been routinely mislabelling containers of fish. And when NCA agents cracked open one of his shipments at Heathrow Airport on February 15, 2017, they discovered 200 kilos of glass eels hidden beneath a load of chilled fish. Khoo was arrested on February 23 as he stepped off a plane from Hong Kong. He was sentenced on March 6 to a two-year suspended prison sentence.

Since Khoo’s arrest, eel smugglers have grown cannier. “The cat and mouse game between authorities and traffickers has intensified in the last few years,” says Andrew Kerr, chairman of the Sustainable Eel Group (SEG), and an expert witness at the Khoo trial. Eel traffickers initially transported illegal fish alongside legitimate catch, mislabelling shipments and forging permits. When young, eels look so similar it is impossible without a DNA test to tell the difference between illegal species – like the endangered European eel – and legal fish, such as the short-finned eel. But as law enforcement began to grow wise to these tactics, the smugglers upped their game.

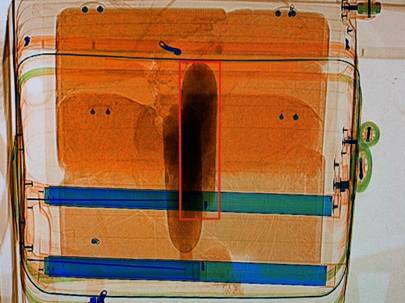

‘Pop-up’ eel stations emerged: disposable properties rented close to where the glass eels were caught so they could be prepared for transport. And traffickers switched from large, easily-inspected containers to portable luggage. Like pet shop goldfish, thousands of writhing glass eels were transported in plastic bags full of water. Airport scanners didn’t automatically flag these bags as suspicious – they looked like bundles of clothes, and security staff were not trained to spot them. The smuggling gangs also realised court proceedings were rarely brought for values less than €50,000 (£45,600). They could stuff suitcases with up to 50,000 glass eel specimens, and usually get away with it.

Until recently, that is. Enforcement has grown tougher. Working with Europol, SEG tracks the number of smugglers arrested during each fishing season, which runs from October to April. This year, 108 were hooked – slightly down on 2018-19 when it was 153, but a big improvement on 2014-15 when only 48 were caught. But these arrests are only “the tip of the iceberg,” warns Kerr. So far, none of the kingpins who control the trade from Hong Kong and mainland China have been netted.

This is very bad news for the European eel. Attempts to breed them in captivity have proved unsuccessful – every eel that ends up in restaurants and supermarkets comes from the same vulnerable wild stocks. And with up to 25 per cent of the glass eel population being trafficked to Asia each year, the trade is deeply unsustainable. It threatens the long-term survival of the species as well as the ecosystems which depend upon them for food. But it also endangers the livelihoods of the farmers, fishermen and smokers who have processed eels for hundreds of years, a vital tradition in Atlantic coastal communities. “If we don’t sort this smuggling out, then the plug is pulled and the water is draining away,” Kerr says.